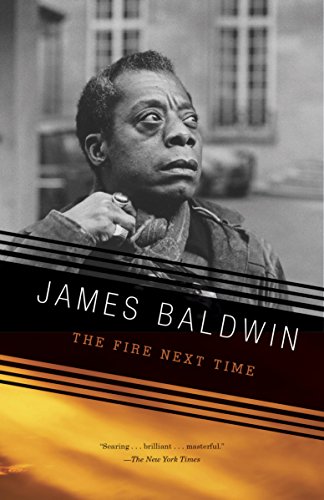

I read James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time over the weekend and found it really powerful. I had wanted to read it for a while and have heard many people compare Te-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, which I found really powerful a few months ago. That increased my drive to prioritize this book and I’m really glad I did, despite being late to the party as it were.

As a book that was written in 1963 in the heart of the civil rights struggle, it struck me just how many of the themes are similar. As I was reading the book I saw the recent news that home ownership for African-Americans was assessed as having made no progress in the past 50 years, since the time The Fire Next Time was written. That bit of info powerfully shaped my reading and experience of what was written in 1963 with such power, art, and conviction.

One of the fascinating dimensions of the book was Baldwin’s critique of the nation of Islam’s approach to peace and justice as he found them to be ideologically on the same ground as white supremacists. But he provides a first-hand account of conversations and interactions I could never experience or observe in person and I found myself riveted in hearing the raw passion and anger and desire for justice. I was also disturbed by the unfiltered hate for whites by some. At this point in my own journey, such realities do not generate as much fear in me as they once may have. Instead, they generate deep sadness and anger of my own. It is true that much has changed for the better in the last 50 years, but it’s also uncomfortable just how much continues to reflect the same patterns of sin and injustice. It’s these realities that make this book important for today as well.

Baldwin gives a strong critique of religion in this book through the lenses of oppression, corruption, and hypocrisy. He offers helpful perspective on how the church – both the black and white churches of the time contributed to the cycles of hatred, violence, and systemic injustice of the time. He clearly turns away from the church as a result, but there’s a lot about his experiences and insights that merit self-reflection for the modern church – especially the way religion and religious institutions can get enslaved by culture and the ideology of the time.

At the core of it, I heard through Baldwin’s anger and contempt for some of these institutions a deep longing for the church to truly be what it should be in the context of such blatant hatred, evil, and injustice. It’s a reality that when the church fails to have anything to say or do that engages meaningfully in matters of injustice and that fails to point to a tangibly different possibility instead of pie in the sky theology, the Church loses its credibility. And Baldwin, stirred with passion and anger, still resists the temptation of ethnic hatred and retaliation in favor of love and sacrifice.

This won’t be the last time I read this book because there’s so much in here that you just can’t absorb or take in one time through.