For access to the research summaries and dissertation let me know.

Before introducing aspects of the theory that emerged in my research and analysis on unequal negotiation and flourishing outcomes, it’s important to add another framework that can illuminate a general range of day-to-day negotiations in organizations, churches, ministries, or even families. Such a framework is helpful because there are a couple of key negotiating factors that shift the dynamics or even change the rules of what is possible (or advisable). Two of these factors are interests and power. Interests and power were two of the five causal conditions for what emerged as the theory’s core phenomenon in unequal negotiation: navigating risk and the threat of loss.

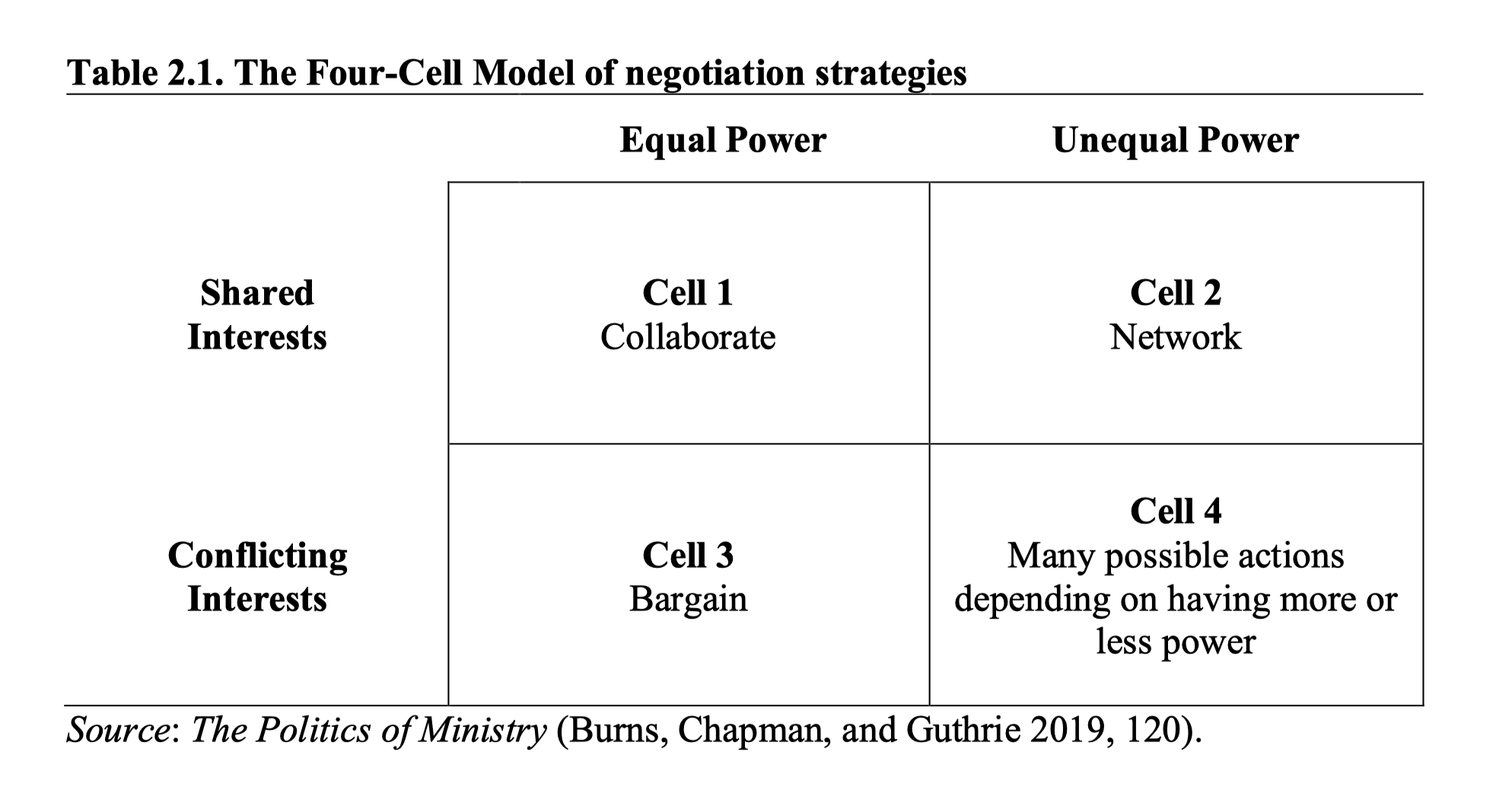

Burns, Chapman, and Guthrie in The Politics of Ministry offer a framework that was helpful in my research and that brings general understanding of the types of negotiations that people experience. They have a 4-cell model organized around interests and power. Here’s a version of the model from their book. Each cell has a general baseline strategy depending on whether interests are shared or conflicting and whether power is equal or unequal.

Burns, Chapman, and Guthrie call unequal negotiations over conflicting interests “Cell 4” negotiations, while “Cell 2” refers to unequal negotiations over shared or complimentary interests (2019, 120). The research I did included both Cell 2 and Cell 4 negotiations because the interviews all began with case studies of unequal power. So both of these cells were included, though the majority of the case studies provided were Cell 4 negotiations given that participants often chose to prioritize an experience that required a significant investment that required facing greater risk. There tends to be more risk when the power is unequal and when each party has different ideas of what needs to happen in the negotiation.

Power inequality in negotiation is somewhat straight forward in this framework. The majority of case studies cited examples of unequal negotiation that were unequal primarily in terms of position or authority. This was especially true in the Southeast Asian interviews – just about each one was rooted in a positional gap of authority. In the American case studies, positional authority was still the dominant variable in power difference between parties, but sometimes power was assigned based on age, gender, ethnicity, competence, communication, age, or resource control. Often there were multiple power variables at work together in both contexts (i.e. white, male, supervisor). Table 4.2 in the dissertation (page 108) provides a more detailed look at how power was assigned by interview participants.

Interests in unequal negotiation can be shared (Cell 2) or conflicting (Cell 4). Contemporary negotiation scholarship exhorts parties to get underneath the “positions” in the negotiation to the underlying interests that are really driving the need for the negotiation. Cell 2 negotiations can still be competitive because it may take some work for parties to realize that they do have shared or complimentary interests. There were case studies shared that started in conflict due to a focus on starting positions or goals, but resulted in mutual flourishing as parties discovered that there was a way for both parties to meet their interests in a satisfactory way. Sometimes this was contingent on the party in power intentionally relating in ways to bridge the power distance so that Cell 2 took on the relational quality of a Cell 1 negotiation. When interests truly did not align, then a more competitive negotiation was common in terms of strategies (Cell 3).

As you can see in Cell 4, strategies and approaches depend on whether one is in the power under or power over negotiating position and what may be needed may fluctuate. I did not focus heavily on tangible negotiating strategy in my research, but instead I was exploring the internal power, identity, and interest processing that contributes to either some measure of personal and relational transformation or a hardening of heart that reinforces and protects interests, identity, and power. These dynamics can be evident in all four cells, but Cell 4 highlights most powerfully the connections between how power, interests, and identity influence one another and contribute to flourishing or diminishing results. For a bit more of a look into the strategic options for power under negotiations in Cell 4 negotiators, I direct you to this helpful blog post which unpacks the model in some of those ways.

Interests can be more than just the motivations for the substantive goals of the negotiation. In my negotiation courses I sometimes frame interests as the things that you are really trying to get as well as the things that you are really working to protect. These things may be quite hidden from others and sometimes they are hidden to the negotiator him or herself as well! But reflection in this area is one way to start getting below the surface to some of what truly might be at work in the substantive or the relational dimensions of the negotiation.

Interests can take many forms. There can be relational interests. There can be personal interests such as status, achievement, and honor. There can be identity interests that are rooted in advancing or protecting different dimensions of perceived identity. There can be interests rooted in human heart issues such as pride, revenge, control, or idolatrous demands. The 4-Cell framework unpacks interests mostly from a framework of what informs the goals of the negotiation. Yet the negotiation itself can awaken or trigger additional interests (relational, identity, heart issues) that can slowly (or quickly) move negotiations from Cell 1 or Cell 2 to Cell 3 or Cell 4.

My research reinforced throughout the process the importance of exploring the ways a party’s power and identity, and their experience of the other party’s power and identity, influenced or changed the interests of the negotiation and the approaches to meeting those interests. Interests can be attached heavily to certain attachments or identities, some of which may not be easily evident. Power itself sometimes becomes an interest in itself to negotiating parties, not just the means by which interests are met. The study’s theory illustrates ways in which identity and power can be either transformed or reinforced, impacting whether outcomes are flourishign or diminishing.

Both Burns, Chapman, and Guthrie’s framework as well as my own research suggest that it is really important to correctly identify what the power dynamic of the negotiation is and what interests are involved. To accurately assess power and interests, it requires humility, honesty, and a vision of sucess that extends beyond our own short term goals. Future posts will explore more of the nuances involved in unequal negotiation related to power, interests, and identity.

For consideration:

When you find yourself in the power under negotiating position, are you aware of the “cell” you are in and what options or strategies might be available to you?

How might understanding of Cell 2 or Cell 4 help you negotiate wisely and ethically?

Where do you see hidden or heart level interests, beyond the obvious motivations related to the explicit goals, influencing your negotiations?

In what ways do you tend to feel threatened in negotiation? What do you regularly find yourself trying to protect?